I Read It in the Book of the Dead Chicago Edu

| ||||||||

| Book of Coming Forth by Mean solar day | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | ||||||||

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

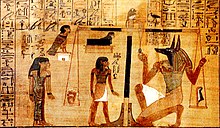

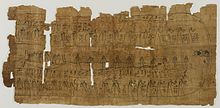

This detail scene, from the Papyrus of Hunefer (c. 1275 BCE), shows the scribe Hunefer's heart being weighed on the scale of Maat against the plume of truth, by the jackal-headed Anubis. The ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods, records the result. If his heart equals exactly the weight of the feather, Hunefer is immune to laissez passer into the afterlife. If not, he is eaten by the waiting chimeric devouring animal Ammit equanimous of the mortiferous crocodile, panthera leo, and hippopotamus. Vignettes such as these were a common illustration in Egyptian books of the expressionless.

The Book of the Dead (Egyptian: 𓂋𓏤𓈒 𓏌𓏤 𓉐𓂋 𓏏𓂻 𓅓 𓉔𓂋 𓅱 𓇳𓏤 ru nu peret em heru; Arabic: كتاب الموتى Kitab al-Mawtaa ) is an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom (effectually 1550 BCE) to around 50 BCE.[one] The original Egyptian proper name for the text, transliterated rw nw prt thousand hrw,[2] is translated as Book of Coming Forth by Day [3] or Book of Emerging Forth into the Light . "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts[four] consisting of a number of magic spells intended to help a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a menstruation of well-nigh 1,000 years.

The Volume of the Expressionless, which was placed in the coffin or burial chamber of the deceased, was part of a tradition of funerary texts which includes the earlier Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, which were painted onto objects, not written on papyrus. Some of the spells included in the volume were drawn from these older works and date to the third millennium BCE. Other spells were equanimous later in Egyptian history, dating to the Third Intermediate Period (11th to 7th centuries BCE). A number of the spells which make upwardly the Volume continued to be separately inscribed on tomb walls and sarcophagi, every bit the spells from which they originated always had been.

There was no single or canonical Book of the Dead. The surviving papyri incorporate a varying selection of religious and magical texts and vary considerably in their illustration. Some people seem to have commissioned their ain copies of the Book of the Dead, perhaps choosing the spells they thought most vital in their own progression to the afterlife. The Volume of the Dead was virtually usually written in hieroglyphic or hieratic script on a papyrus scroll, and often illustrated with vignettes depicting the deceased and their journey into the afterlife.

The finest extant example of the Egyptian Volume of the Dead in antiquity is the Papyrus of Ani. Ani was an Egyptian scribe. Information technology was discovered past Sir E. A. Wallis Budge in 1888 and was taken to the British Museum, where information technology currently resides.

Development [edit]

Part of the Pyramid Texts, a precursor of the Book of the Dead, inscribed on the tomb of Teti

The Book of the Dead developed from a tradition of funerary manuscripts dating dorsum to the Egyptian Old Kingdom. The first funerary texts were the Pyramid Texts, first used in the Pyramid of King Unas of the 5th Dynasty, around 2400 BCE.[5] These texts were written on the walls of the burying chambers inside pyramids, and were exclusively for the use of the pharaoh (and, from the sixth Dynasty, the queen). The Pyramid Texts were written in an unusual hieroglyphic manner; many of the hieroglyphs representing humans or animals were left incomplete or drawn mutilated, almost likely to prevent them causing any harm to the dead pharaoh.[half dozen] The purpose of the Pyramid Texts was to help the dead king take his place amongst the gods, in particular to reunite him with his divine father Ra; at this period the afterlife was seen every bit existence in the sky, rather than the underworld described in the Book of the Dead.[6] Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, the Pyramid Texts ceased to be an exclusively regal privilege, and were adopted past regional governors and other high-ranking officials.

In the Centre Kingdom, a new funerary text emerged, the Bury Texts. The Coffin Texts used a newer version of the linguistic communication, new spells, and included illustrations for the first fourth dimension. The Coffin Texts were near usually written on the inner surfaces of coffins, though they are occasionally institute on tomb walls or on papyri.[vi] The Coffin Texts were available to wealthy private individuals, vastly increasing the number of people who could expect to participate in the afterlife; a procedure which has been described as the "democratization of the afterlife".[7]

The Book of the Expressionless first adult in Thebes toward the showtime of the 2d Intermediate Period, effectually 1700 BCE. The earliest known occurrence of the spells included in the Book of the Expressionless is from the coffin of Queen Mentuhotep, of the 13th Dynasty, where the new spells were included amongst older texts known from the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts. Some of the spells introduced at this time claim an older provenance; for instance the rubric to spell 30B states that it was discovered by the Prince Hordjedef in the reign of Rex Menkaure, many hundreds of years before it is attested in the archaeological record.[8]

By the 17th Dynasty, the Book of the Dead had go widespread not only for members of the royal family, simply courtiers and other officials as well. At this phase, the spells were typically inscribed on linen shrouds wrapped around the dead, though occasionally they are found written on coffins or on papyrus.[ix]

The New Kingdom saw the Book of the Dead develop and spread farther. The famous Spell 125, the 'Weighing of the Eye', is outset known from the reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose Three, c.1475 BCE. From this flow onward the Volume of the Dead was typically written on a papyrus scroll, and the text illustrated with vignettes. During the 19th Dynasty in particular, the vignettes tended to be lavish, sometimes at the expense of the surrounding text.[10]

In the Third Intermediate Period, the Book of the Dead started to appear in hieratic script, as well every bit in the traditional hieroglyphics. The hieratic scrolls were a cheaper version, lacking illustration apart from a single vignette at the outset, and were produced on smaller papyri. At the same time, many burials used additional funerary texts, for case the Amduat.[xi]

During the 25th and 26th Dynasties, the Book of the Dead was updated, revised and standardised. Spells were ordered and numbered consistently for the showtime time. This standardised version is known today every bit the 'Saite recension', after the Saite (26th) Dynasty. In the Tardily period and Ptolemaic menstruum, the Volume of the Dead connected to be based on the Saite recension, though increasingly abbreviated towards the cease of the Ptolemaic period. New funerary texts appeared, including the Volume of Breathing and Book of Traversing Eternity. The final use of the Book of the Expressionless was in the 1st century BCE, though some artistic motifs drawn from it were still in use in Roman times.[12]

Spells [edit]

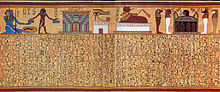

The mystical Spell 17, from the Papyrus of Ani. The vignette at the summit illustrates, from left to right, the god Heh every bit a representation of the Sea; a gateway to the realm of Osiris; the Center of Horus; the celestial moo-cow Mehet-Weret; and a human head rising from a coffin, guarded past the four Sons of Horus.[13]

The Volume of the Dead is made upwardly of a number of individual texts and their accompanying illustrations. Most sub-texts begin with the discussion ro, which can hateful "mouth", "speech", "spell", "utterance", "incantation", or "affiliate of a volume". This ambiguity reflects the similarity in Egyptian idea between ritual voice communication and magical power.[14] In the context of the Book of the Dead, it is typically translated every bit either chapter or spell. In this article, the word spell is used.

At present, some 192 spells are known,[15] though no single manuscript contains them all. They served a range of purposes. Some are intended to requite the deceased mystical knowledge in the afterlife, or perhaps to identify them with the gods: for case, Spell 17 is an obscure and lengthy description of the god Atum.[16] Others are incantations to ensure the different elements of the expressionless person'south being were preserved and reunited, and to give the deceased control over the earth around him. Even so others protect the deceased from diverse hostile forces or guide him through the underworld by various obstacles. Famously, two spells as well deal with the judgement of the deceased in the Weighing of the Heart ritual.

Such spells as 26–30, and sometimes spells vi and 126, relate to the heart and were inscribed on scarabs.[17]

The texts and images of the Book of the Dead were magical also as religious. Magic was as legitimate an activity as praying to the gods, even when the magic was aimed at controlling the gods themselves.[18] Indeed, there was footling distinction for the Ancient Egyptians between magical and religious practice.[nineteen] The concept of magic (heka) was also intimately linked with the spoken and written word. The act of speaking a ritual formula was an act of creation;[20] there is a sense in which action and speech were one and the same matter.[xix] The magical power of words extended to the written give-and-take. Hieroglyphic script was held to accept been invented by the god Thoth, and the hieroglyphs themselves were powerful. Written words conveyed the total force of a spell.[xx] This was even true when the text was abbreviated or omitted, every bit oft occurred in later Book of the Dead scrolls, particularly if the accompanying images were present.[21] The Egyptians also believed that knowing the name of something gave power over information technology; thus, the Book of the Dead equips its owner with the mystical names of many of the entities he would encounter in the afterlife, giving him power over them.[22]

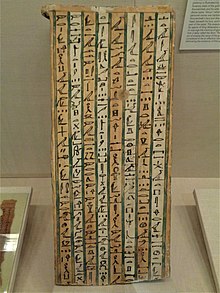

Egyptian Book of the Dead, painted on a coffin fragment (c. 747–656 BCE): Spell 79 (attaching the soul to the body); and Spell eighty (preventing breathless speech)

The spells of the Volume of the Dead made use of several magical techniques which can too be seen in other areas of Egyptian life. A number of spells are for magical amulets, which would protect the deceased from harm. In addition to being represented on a Book of the Dead papyrus, these spells appeared on amulets wound into the wrappings of a mummy.[xviii] Everyday magic made use of amulets in huge numbers. Other items in direct contact with the body in the tomb, such as headrests, were also considered to have amuletic value.[23] A number of spells as well refer to Egyptian beliefs nearly the magical healing ability of saliva.[18]

Organization [edit]

Almost every Volume of the Dead was unique, containing a different mixture of spells drawn from the corpus of texts available. For most of the history of the Volume of the Dead there was no defined order or structure.[24] In fact, until Paul Barguet's 1967 "pioneering study" of common themes between texts,[25] Egyptologists concluded there was no internal structure at all.[26] It is only from the Saite period (26th Dynasty) onwards that in that location is a divers order.[27]

The Books of the Dead from the Saite period tend to organize the Chapters into iv sections:

- Chapters 1–16 The deceased enters the tomb and descends to the underworld, and the trunk regains its powers of movement and speech.

- Capacity 17–63 Explanation of the mythic origin of the gods and places. The deceased is made to live again and then that he may ascend, reborn, with the forenoon dominicus.

- Chapters 64–129 The deceased travels across the sky in the sun ark as 1 of the blessed expressionless. In the evening, the deceased travels to the underworld to appear before Osiris.

- Chapters 130–189 Having been vindicated, the deceased assumes power in the universe equally one of the gods. This section too includes assorted chapters on protective amulets, provision of nutrient, and important places.[26]

Egyptian concepts of death and afterlife [edit]

A vignette in The Papyrus of Ani, from Spell 30B: Spell For Not Letting Ani's Heart Create Opposition Confronting Him, in the Gods' Domain, which contains a depiction of the ba of the deceased

The spells in the Book of the Dead depict Egyptian beliefs well-nigh the nature of death and the afterlife. The Book of the Dead is a vital source of data about Egyptian beliefs in this area.

Preservation [edit]

One aspect of decease was the disintegration of the various kheperu, or modes of existence.[28] Funerary rituals served to re-integrate these different aspects of existence. Mummification served to preserve and transform the physical body into sah, an idealised grade with divine aspects;[29] the Book of the Dead contained spells aimed at preserving the trunk of the deceased, which may have been recited during the procedure of mummification.[30] The heart, which was regarded as the attribute of being which included intelligence and memory, was also protected with spells, and in example anything happened to the physical eye, it was mutual to bury jewelled heart scarabs with a body to provide a replacement. The ka, or life-force, remained in the tomb with the dead trunk, and required sustenance from offerings of food, water and incense. In instance priests or relatives failed to provide these offerings, Spell 105 ensured the ka was satisfied.[31] The name of the dead person, which constituted their individuality and was required for their continued existence, was written in many places throughout the Book, and spell 25 ensured the deceased would remember their ain name.[32] The ba was a free-ranging spirit aspect of the deceased. It was the ba, depicted as a human-headed bird, which could "become forth past day" from the tomb into the world; spells 61 and 89 acted to preserve information technology.[33] Finally, the shut, or shadow of the deceased, was preserved by spells 91, 92 and 188.[34] If all these aspects of the person could be variously preserved, remembered, and satiated, then the dead person would live on in the form of an akh. An akh was a blest spirit with magical powers who would dwell among the gods.[35]

Afterlife [edit]

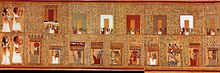

The nature of the afterlife which the expressionless people enjoyed is difficult to define, considering of the differing traditions inside Aboriginal Egyptian faith. In the Volume of the Expressionless, the expressionless were taken into the presence of the god Osiris, who was confined to the subterranean Duat. There are besides spells to enable the ba or akh of the dead to join Ra as he travelled the heaven in his sun-barque, and help him fight off Apep.[36] Too as joining the Gods, the Book of the Dead also depicts the expressionless living on in the 'Field of Reeds', a paradisiac likeness of the real world.[37] The Field of Reeds is depicted as a lush, plentiful version of the Egyptian style of living. In that location are fields, crops, oxen, people and waterways. The deceased person is shown encountering the Corking Ennead, a grouping of gods, equally well as his or her own parents. While the delineation of the Field of Reeds is pleasant and plentiful, it is besides articulate that manual labour is required. For this reason burials included a number of statuettes named shabti, or subsequently ushebti. These statuettes were inscribed with a spell, likewise included in the Book of the Expressionless, requiring them to undertake any manual labour that might exist the owner's duty in the afterlife.[38] It is likewise articulate that the dead not only went to a place where the gods lived, but that they acquired divine characteristics themselves. In many occasions, the deceased is mentioned as "The Osiris – [Name]" in the Book of the Dead.

Ii 'gate spells'. On the height register, Ani and his married woman face the 'vii gates of the Firm of Osiris'. Below, they run into 10 of the 21 'mysterious portals of the House of Osiris in the Field of Reeds'. All are guarded by unpleasant protectors.[39]

The path to the afterlife every bit laid out in the Book of the Expressionless was a hard one. The deceased was required to pass a series of gates, caverns and mounds guarded by supernatural creatures.[xl] These terrifying entities were armed with enormous knives and are illustrated in grotesque forms, typically every bit human figures with the heads of animals or combinations of different ferocious beasts. Their names—for instance, "He who lives on snakes" or "He who dances in blood"—are equally grotesque. These creatures had to be pacified past reciting the appropriate spells included in the Book of the Dead; once pacified they posed no further threat, and could even extend their protection to the expressionless person.[41] Some other breed of supernatural creatures was 'slaughterers' who killed the unrighteous on behalf of Osiris; the Book of the Dead equipped its possessor to escape their attentions.[42] Besides as these supernatural entities, there were also threats from natural or supernatural animals, including crocodiles, snakes, and beetles.[43]

Judgment [edit]

If all the obstacles of the Duat could exist negotiated, the deceased would be judged in the "Weighing of the Heart" ritual, depicted in Spell 125. The deceased was led past the god Anubis into the presence of Osiris. There, the dead person swore that he had not committed any sin from a list of 42 sins,[44] reciting a text known as the "Negative Confession". Then the expressionless person's centre was weighed on a pair of scales, confronting the goddess Maat, who embodied truth and justice. Maat was often represented by an ostrich feather, the hieroglyphic sign for her name.[45] At this betoken, there was a risk that the deceased'due south heart would conduct witness, owning up to sins committed in life; Spell 30B guarded against this eventuality. If the scales balanced, this meant the deceased had led a good life. Anubis would have them to Osiris and they would find their place in the afterlife, becoming maa-kheru, meaning "vindicated" or "true of voice".[46] If the heart was out of balance with Maat, then another fearsome fauna called Ammit, the Devourer, stood ready to eat information technology and put the dead person's afterlife to an early on and unpleasant terminate.[47]

This scene is remarkable not but for its vividness but every bit one of the few parts of the Book of the Dead with any explicit moral content. The judgment of the dead and the Negative Confession were a representation of the conventional moral code which governed Egyptian lodge. For every "I have not..." in the Negative Confession, it is possible to read an unexpressed "Thou shalt not".[48] While the X Commandments of Jewish and Christian ethics are rules of behave laid down by a perceived divine revelation, the Negative Confession is more a divine enforcement of everyday morality.[49] Views differ among Egyptologists about how far the Negative Confession represents a moral accented, with ethical purity being necessary for progress to the Afterlife. John Taylor points out the diction of Spells 30B and 125 suggests a pragmatic arroyo to morality; by preventing the heart from contradicting him with whatsoever inconvenient truths, information technology seems that the deceased could enter the afterlife even if their life had not been entirely pure.[47] Ogden Goelet says "without an exemplary and moral existence, there was no hope for a successful afterlife",[48] while Geraldine Pinch suggests that the Negative Confession is substantially similar to the spells protecting from demons, and that the success of the Weighing of the Heart depended on the mystical knowledge of the truthful names of the judges rather than on the deceased'due south moral behaviour.[50]

Producing a Book of the Dead [edit]

Part of the Book of the Dead of Pinedjem II. The text is hieratic, except for hieroglyphics in the vignette. The use of ruddy pigment, and the joins between papyrus sheets, are likewise visible.

A Volume of the Dead was produced to gild by scribes. They were commissioned by people in preparation for their own funerals, or past the relatives of someone recently deceased. They were expensive items; i source gives the cost of a Book of the Expressionless scroll as ane deben of silver,[51] maybe half the annual pay of a labourer.[52] Papyrus itself was evidently costly, equally at that place are many instances of its re-apply in everyday documents, creating palimpsests. In one case, a Volume of the Dead was written on 2d-manus papyrus.[53]

About owners of the Volume of the Dead were evidently part of the social elite; they were initially reserved for the majestic family unit, but subsequently papyri are found in the tombs of scribes, priests and officials. Most owners were men, and by and large the vignettes included the owner'due south married woman as well. Towards the beginning of the history of the Book of the Dead, there are roughly 10 copies belonging to men for every 1 for a woman. Notwithstanding, during the 3rd Intermediate Flow, 2 were for women for every 1 for a homo; and women endemic roughly a third of the hieratic papyri from the Late and Ptolemaic Periods.[54]

The dimensions of a Volume of the Dead could vary widely; the longest is 40 chiliad long while some are every bit brusque every bit one m. They are composed of sheets of papyrus joined together, the individual papyri varying in width from fifteen cm to 45 cm. The scribes working on Book of the Dead papyri took more than care over their piece of work than those working on more than mundane texts; care was taken to frame the text within margins, and to avoid writing on the joints between sheets. The words peret em heru, or coming along by day sometimes appear on the reverse of the outer margin, perhaps acting as a label.[53]

Books were ofttimes prefabricated in funerary workshops, with spaces being left for the name of the deceased to be written in later on.[55] For instance, in the Papyrus of Ani, the name "Ani" appears at the tiptop or bottom of a column, or immediately following a rubric introducing him equally the speaker of a block of text; the proper name appears in a different handwriting to the residue of the manuscript, and in some places is mis-spelt or omitted entirely.[52]

The text of a New Kingdom Volume of the Dead was typically written in cursive hieroglyphs, most ofttimes from left to right, only also sometimes from correct to left. The hieroglyphs were in columns, which were separated by black lines – a like arrangement to that used when hieroglyphs were carved on tomb walls or monuments. Illustrations were put in frames to a higher place, below, or between the columns of text. The largest illustrations took upwardly a full page of papyrus.[56]

From the 21st Dynasty onward, more than copies of the Book of the Expressionless are constitute in hieratic script. The calligraphy is similar to that of other hieratic manuscripts of the New Kingdom; the text is written in horizontal lines across wide columns (often the column size corresponds to the size of the papyrus sheets of which a coil is made up). Occasionally a hieratic Volume of the Dead contains captions in hieroglyphic.

The text of a Book of the Expressionless was written in both black and blood-red ink, regardless of whether it was in hieroglyphic or hieratic script. Most of the text was in blackness, with cherry-red ink used for the titles of spells, opening and closing sections of spells, the instructions to perform spells correctly in rituals, and also for the names of dangerous creatures such every bit the demon Apep.[57] The black ink used was based on carbon, and the cerise ink on ochre, in both cases mixed with water.[58]

The manner and nature of the vignettes used to illustrate a Book of the Dead varies widely. Some contain lavish color illustrations, fifty-fifty making employ of gold leaf. Others contain only line drawings, or 1 simple illustration at the opening.[59]

Book of the Dead papyri were often the work of several dissimilar scribes and artists whose work was literally pasted together.[53] It is usually possible to identify the mode of more than one scribe used on a given manuscript, fifty-fifty when the manuscript is a shorter one.[57] The text and illustrations were produced by unlike scribes; there are a number of Books where the text was completed merely the illustrations were left empty.[60]

Book of the Expressionless of Sobekmose, the Goldworker of Amun, 31.1777e, Brooklyn Museum

Discovery, translation, estimation and preservation [edit]

The existence of the Book of the Expressionless was known as early as the Middle Ages, well before its contents could be understood. Since it was found in tombs, it was plainly a certificate of a religious nature, and this led to the widespread but mistaken conventionalities that the Book of the Dead was the equivalent of a Bible or Qur'an.[61] [62]

In 1842 Karl Richard Lepsius published a translation of a manuscript dated to the Ptolemaic era and coined the name "Book of The Dead" (das Todtenbuch). He also introduced the spell numbering organization which is still in use, identifying 165 different spells.[15] Lepsius promoted the idea of a comparative edition of the Book of the Dead, drawing on all relevant manuscripts. This project was undertaken past Édouard Naville, starting in 1875 and completed in 1886, producing a iii-volume work including a selection of vignettes for every 1 of the 186 spells he worked with, the more meaning variations of the text for every spell, and commentary. In 1867 Samuel Birch of the British Museum published the offset extensive English translation.[63] In 1876 he published a photographic copy of the Papyrus of Nebseny.[64]

The work of E. A. Wallis Budge, Birch's successor at the British Museum, is still in wide circulation – including both his hieroglyphic editions and his English translations of the Papyrus of Ani, though the latter are at present considered inaccurate and out-of-date.[65] More recent translations in English have been published by T. Grand. Allen (1974) and Raymond O. Faulkner (1972).[66] Every bit more piece of work has been washed on the Volume of the Expressionless, more spells take been identified, and the full at present stands at 192.[15]

In the 1970s, Ursula Rößler-Köhler at the University of Bonn began a working group to develop the history of Book of the Expressionless texts. This after received sponsorship from the German land of Due north Rhine-Westphalia and the German language Inquiry Foundation, in 2004 coming under the auspices of the German Academies of Sciences and Arts. Today the Book of the Expressionless Project, as information technology is called, maintains a database of documentation and photography covering 80% of extant copies and fragments from the corpus of Book of the Dead texts, and provides electric current services to Egyptologists.[67] It is housed at the University of Bonn, with much cloth available online.[68] Affiliated scholars are authoring a series of monograph studies, the Studien zum Altägyptischen Totenbuch, alongside a serial that publishes the manuscripts themselves, Handschriften des Altägyptischen Totenbuches.[69] Both are in print by Harrassowitz Verlag. Orientverlag has released another series of related monographs, Totenbuchtexte, focused on analysis, synoptic comparison, and textual criticism.

Research piece of work on the Book of the Dead has ever posed technical difficulties thank you to the need to re-create very long hieroglyphic texts. Initially, these were copied out past hand, with the assistance either of tracing newspaper or a camera lucida. In the mid-19th century, hieroglyphic fonts became available and made lithographic reproduction of manuscripts more than feasible. In the present day, hieroglyphics can be rendered in desktop publishing software and this, combined with digital print technology, means that the costs of publishing a Volume of the Dead may be considerably reduced. However, a very big corporeality of the source material in museums around the world remains unpublished.[seventy]

Chronology [edit]

- c. 3150 BCE – Get-go preserved hieroglyphs, on minor labels in the tomb of a king buried (in tomb U-j) at Abydos

- c. 3000 BCE – The beginning of the numbered dynasties of kings of aboriginal Egypt

- c. 2345 BCE – Kickoff royal pyramid, of Rex Unas, to contain the Pyramid Texts, carved precursors (intended only for the king) to the funerary literature from which the Book of the Dead ultimately adult

- c. 2100 BCE – Beginning Coffin Texts, developed from the Pyramid Texts and for a time painted on the coffins of commoners. Many spells of the Book of the Dead are closely derived from them

- c. 1600 BCE – Earliest spells of the Volume of the Dead, on the coffin of Queen Menthuhotep, an ancestor of kings from the New Kingdom

- c. 1550 BCE – From this time onward to the commencement of the New Kingdom, papyrus copies of the Book of the Dead are used instead of inscribing spells on the walls of the tombs

- c. 600 BCE – Approximately when the order of the spells became standard

- 42–553 CE – Christianity spreads to Egypt, gradually replacing the native religion as successive emperors alternately tolerate or suppress them, culminating in the concluding temple at Philae (besides site of the last known religious inscription in demotic, dating from 452) being closed past order of Emperor Justinian in 533

- 2nd century CE – Perchance the concluding copies of the Book of the Dead were produced, merely it is a poorly documented era of history

- 1798 CE – Napoleon's invasion of Arab republic of egypt encourages European interests in ancient Egypt; 1799, Vivant Denon was handed a copy of the Book of the Dead

- 1805 CE – J. Marc Buck makes the first publication, on 18 plates, of a Book of the Dead, Copie figurée d'united nations Roleau de Papyrus trouvé à Thèbes dans un Thombeau des Rois, accompagnèe d'une discover descriptive, Paris, Levrault

- 1822 CE – Jean-François Champollion announces the key to the decipherment of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, afterwards developed in his afterwards publications, the about all-encompassing after his death in 1832

- 1842 CE – Lepsius publishes the offset major study of the Volume of the Dead, begins the numbering of the spells or capacity, and brings the name "Book of the Expressionless" into general circulation[71]

See besides [edit]

- Aaru

- Bardo Thodol (Tibetan volume of the dead)

- Book of the Dead of Amen-em-lid

- Book of the Dead of Qenna

- Ghosts in ancient Egyptian civilisation

- Necronomicon (H. P. Lovecraft's book of the dead)

- Qenna

- Shūjin eastward no Pert-em-Hru

- Joseph Smith Papyri. Drove includes Books of the Dead of TaSheritMin, Nefer-ir-nebu and Amenhotep.

References [edit]

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.54

- ^ Allen, 2000. p.316

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.55; or maybe "Utterances of Going Along by Day", D'Auria 1988, p. 187

- ^ The Egyptian Book of the Dead by Anonymous (2 Jun 2014) ...with an introduction by Paul Mirecki (Seven)

- ^ Faulkner p. 54

- ^ a b c Taylor 2010, p. 54

- ^ D'Auria et al p.187

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.34

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 55

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.35–7

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.57–eight

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.59 60

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.51

- ^ Faulkner 1994, p.145; Taylor 2010, p.29

- ^ a b c Faulkner 1994, p.18

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.51, 56

- ^ Hornung, Erik; David Lorton (15 June 1999). The ancient Egyptian books of the afterlife . Cornell University Printing. p. 14. ISBN978-0-8014-8515-two.

- ^ a b c Faulkner 1994, p.146

- ^ a b Faulkner 1994, p.145

- ^ a b Taylor 2010, p.30

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.32–3; Faulkner 1994, p.148

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.thirty–ane

- ^ Pinch 1994, p.104–5

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.55

- ^ Barguet, Paul (1967). Le Livre des morts des anciens Égyptiens (in French). Paris: Éditions du Cerf.

- ^ a b Faulkner 1994, p.141

- ^ Taylor, p.58

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.16-17

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.17 & xx

- ^ For case, Spell 154. Taylor 2010, p.161

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.163-iv

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.163

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.17, 164

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.164

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.17

- ^ Spells 100–2, 129–131 and 133–136. Taylor 2010, p.239–241

- ^ Spells 109, 110 and 149. Taylor 2010, p.238–240

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.242–245

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.143

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.135

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.136–7

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 188

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 184–7

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 208

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.209

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.215

- ^ a b Taylor 2010, p.212

- ^ a b Faulkner 1994, p.14

- ^ Taylor 2010,p.204–v

- ^ Pinch 1994, p.155

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 62

- ^ a b Faulkner 1994, p. 142

- ^ a b c Taylor 2010, p. 264

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 62–63

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 267

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 266

- ^ a b Taylor 2010, p. 270

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 277

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 267–viii

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 268

- ^ Faulkner 1994, p.xiii

- ^ Taylor 210, p.288 ix

- ^ "Egypt's Identify in Universal History", Vol 5, 1867

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.289 92

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.291

- ^ Hornung 1999, p.15–16

- ^ Müller-Roth 2010, p.190-191

- ^ Das Altagyptische Totenbuch: Ein Digitales Textzeugenarchiv (external link)

- ^ Müller-Roth 2010, p.191

- ^ Taylor 2010, p.292–7

- ^ Kemp, Barry (2007). How to Read the Egyptian Volume of the Dead. New York: Granta Publications. pp. 112–113.

Further reading [edit]

- Allen, James P., Middle Egyptian – An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, beginning edition, Cambridge Academy Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-77483-7

- Allen, Thomas George, The Egyptian Book of the Expressionless: Documents in the Oriental Institute Museum at the Academy of Chicago. University of Chicago Printing, Chicago 1960.

- Allen, Thomas George, The Book of the Dead or Going Forth by 24-hour interval. Ideas of the Ancient Egyptians Concerning the Time to come equally Expressed in Their Ain Terms, SAOC vol. 37; University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1974.

- Assmann, Jan (2005) [2001]. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4241-9

- D'Auria, S (et al.) Mummies and Magic: the Funerary Arts of Aboriginal Egypt. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1989. ISBN 0-87846-307-0

- Faulkner, Raymond O; Andrews, Carol (editor), The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. University of Texas Printing, Austin, 1972.

- Faulkner, Raymond O (translator); von Dassow, Eva (editor), The Egyptian Book of the Expressionless, The Book of Going forth by Day. The Outset Authentic Presentation of the Consummate Papyrus of Ani. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1994.

- Hornung, Erik; Lorton, D (translator), The Aboriginal Egyptian books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8014-8515-0

- Lapp, Grand, The Papyrus of Nu (Catalogue of Books of the Dead in the British Museum). British Museum Press, London, 1997.

- Müller-Roth, Marcus, "The Book of the Expressionless Project: By, present and future." British Museum Studies in Aboriginal Egypt and Sudan fifteen (2010): 189-200.

- Niwinski, Andrzej, Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and tenth Centuries B.C.. OBO vol. 86; Universitätsverlag, Freiburg, 1989.

- Pinch, Geraldine, Magic in Ancient Arab republic of egypt. British Museum Press, London, 1994. ISBN 0-7141-0971-1

- Taylor, John H. (Editor), Ancient Egyptian Volume of the Dead: Journey through the afterlife. British Museum Press, London, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7141-1993-ix

External links [edit]

- The Mummy Bedchamber Brooklyn Museum Exhibit

- Das altägyptische Totenbuch - ein digitales Textzeugenarchiv Complete digital archive of all witnesses for the Book of the Dead (with descriptions of the (c. 3000) objects and (c. xx,000) images)

- Online Readable Text, with several images and reproductions of Egyptian papyri

- Papyrus of Hunefer, with many scenes and their formula English translations, from the copy now in the British Museum

- Video: British Museum curator introduces the Book of the Dead

alexanderyoulthad95.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_the_Dead

Enregistrer un commentaire for "I Read It in the Book of the Dead Chicago Edu"